A Visit to Philipsburg Manor

“Cross the millpond bridge to Philipsburg Manor, a mill and trading complex where an enslaved community lived and labored for generations.

Learn about the enslaved individuals who worked on the property in the year 1750, and whose family relationships and personal histories are revealed in primary documents.

Step into the gristmill and learn about the life of Caesar, the enslaved miller, whose unmatched expertise contributed to the wealth of the Philipse family but benefited him not at all.

Visit the dairy in the cellar of the Manor House, where a commercial butter production was operated by Dina, Massey and Sue, three of the women enslaved by the Philipses at the site.

Discover the many ways the enslaved community at Philipsburg Manor maintained family networks, shared their cultural heritage, and expressed their fundamental humanity in opposition to the inhumane system that bound them.”

So reads the Philipsburg Manor Website.

It’s quite close to where I live. Walk-able even, if you don’t mind a four-hour round-trip walk, mostly along the Old Croton Aqueduct Trail. I’ve done it a few times.

I’ve been to Philipsburg Manor a number of times, usually with visiting friends or families. We usually do the tour and then leave so I haven’t had the opportunity to just walk around and take pictures. Above: Approaching the bridge to the property.

Recently, however, I became a member of Historic Hudson Valley, which, among a host of other benefits gives me free tours of Philipsburg Manor. So I went over to have a look around.

I was still required to register for the tour, which I took as far as the mill. The next stop was the interior of the house, which I’d seen this a number of times already and didn’t’ feel the need to see it again. In any case they don’t allow photography inside the house. So, I left the tour and went for a walk around.

The three main buildings. From left to right: the mill; the manor house; the stable. There’s actually a fourth one (A tenant farmer’s dwelling), but you can’t see it from here.

One of the re-enactors/guides crossing the walkway. Possibly a better view of the main buildings.

The Pocantico River flows into the millpond, over the water wheel and then out to the nearby Hudson River.

As I was waiting for the tour to begin, I spotted these kayakers (if that’s the right word for someone in a kayak?) and thought that, with the mill in the background it would make a nice photograph.

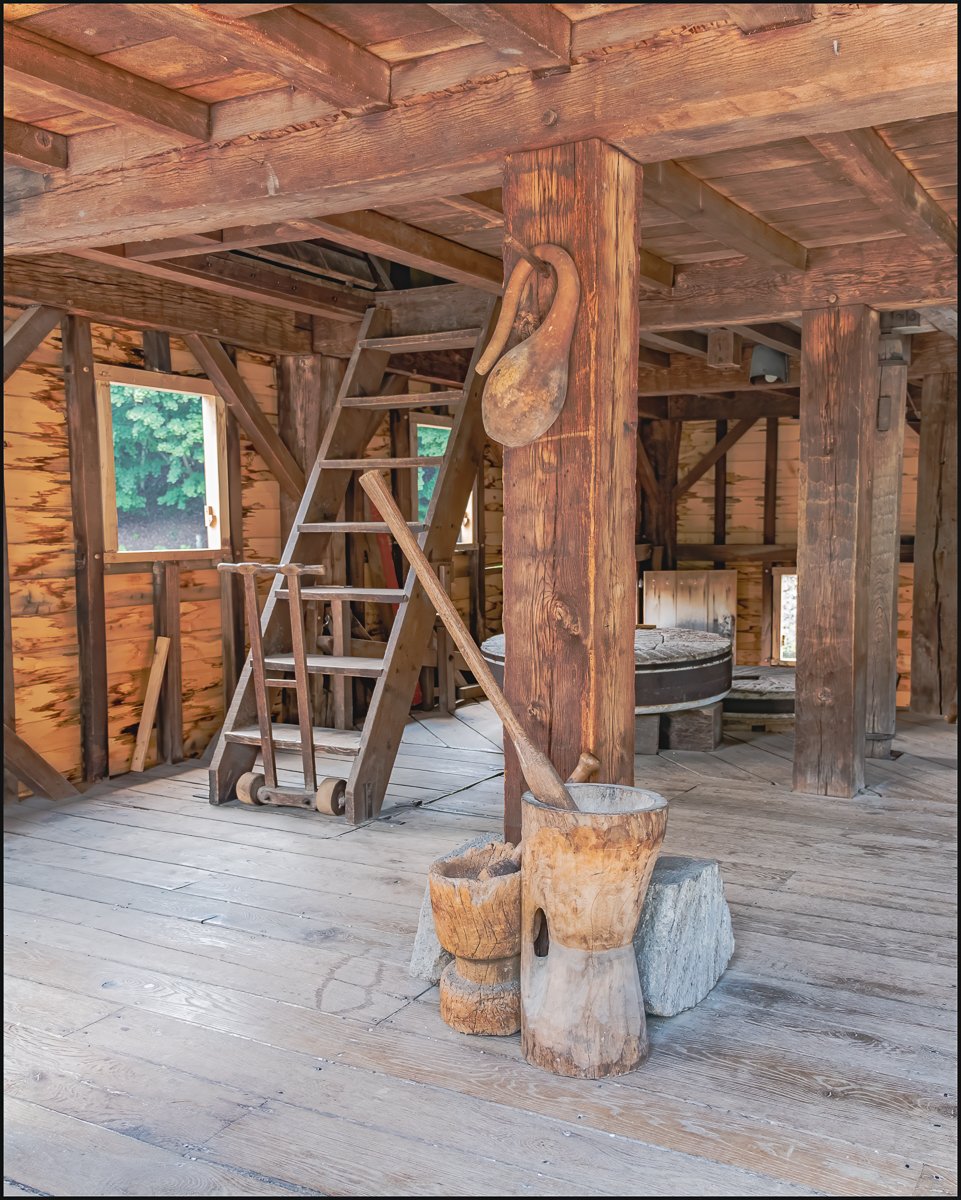

One of the highlights of the tour was the Mill, a working Grist Mill where you could usually see corn being turned into flour. Unfortunately not the day I was there. Apparently, the Pocantico River/Millponds were at a very low level. This, combined with silting meant that there was not enough water to power the mill. Too bad. But I can come again and at least I was able to get some interior shots.

Of course, where you have a lot of corn and flour, you also tend to get lots of rats, mice and other vermin. So you also need something to deal with them: a cat.

This picture is a little misleading. It gives the impression that I was walking around and came across a sleeping cat. That was not at all the case. A small crowd of visitors was milling (get it? milling?) around this millstone while the guide was explaining how it worked. In typical cat fashion the cat walked through all the people, jumped onto the millstone, lay down and fell asleep. You’ve got to love cats and, as a cat owner myself, I certainly do.

The Coopers House

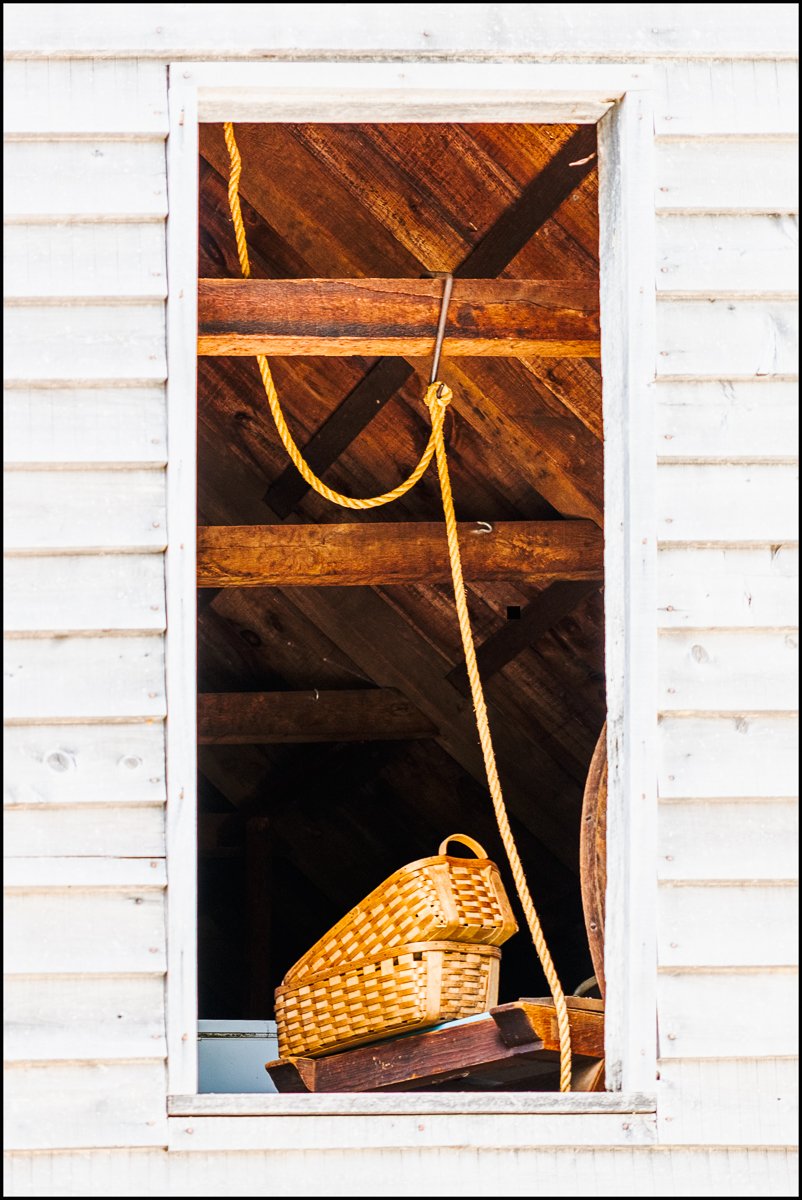

You can see it in the first picture to the left of the mill. It’s attached to the mill, but serves a completely different purpose. After the corn was milled it was put into sacks and barrels, transferred to boat on the Pocantico River. From there it made a short trip to the Hudson River and then along the river to be sold and/or delivered.

“The word “cooper” is derived from Middle Dutch or Middle Low German kūper ‘cooper’ from kūpe ‘cask’, in turn from Latin cupa ‘tun, barrel’. Everything a cooper produces is referred to collectively as cooperage. A cask is any piece of cooperage containing a bouge, bilge, or bulge in the middle of the container. A barrel is a type of cask, so the terms “barrel-maker” and “barrel-making” refer to just one aspect of a cooper’s work. The facility in which casks are made is also referred to as a cooperage.

…

Traditionally, a cooper is someone who makes wooden, staved vessels, held together with wooden or metal hoops and possessing flat ends or heads. Examples of a cooper’s work include casks, barrels, buckets, tubs, butter churns, vats, hogsheads, firkins, tierces, rundlets, puncheons, pipes, tuns, butts, troughs, pins and breakers. Traditionally, a hooper was the man who fitted the wooden or metal hoops around the barrels or buckets that the cooper had made, essentially an assistant to the cooper. The English name Hooper is derived from that profession. With time, many coopers took on the role of the hooper themselves.” (Wikipedia).

“The manor dates from 1693, when wealthy Province of New York merchant Frederick Philipse was granted a charter for 52,000 acres (21,000 ha) along the Hudson River by the British Crown. He built a facility at the confluence of the Pocantico and Hudson Rivers as a provisioning depot for the family Atlantic Sea trade and as headquarters for a worldwide shipping operation. For more than thirty years, Frederick and his wife Margaret, and later his son Adolph shipped hundreds of African men, women, and children as slaves across the Atlantic.

By the mid 18th century, the Philipse family had one of the largest slaveholdings in the colonial North. The family seat of Philipsburg Manor was Philipse Manor Hall in Yonkers

The manor was tenanted by farmers of various European backgrounds and operated by enslaved Africans. (In 1750, twenty-three enslaved men, women, and children lived and worked at the manor.)

At the outbreak of the American Revolutionary War, the Philipses supported the British, and their landholdings were seized and auctioned off. The manor house was used during the war, most notably by British General Sir Henry Clinton during military activities in 1779. It was there that he wrote what is now known as the Philipsburg Proclamation, which declared all Patriot-owned slaves to be free, and that blacks taken prisoner while serving in Patriot forces would be sold into slavery. (Wikipedia)”

Named a National Historic Landmark in 1961, the farm features this stone manor house filled with a collection of 17th- and 18th-century period furnishings. I believe it’s the only original building on the site, the remainder being reproductions.

A Dutch style barn with lots of wood and straw, and some interesting objects – a cart; a yoke; a drying rack; some barrels; a milk churn; a number of wooden rakes; a plough etc. More or less what you’d expect to find.

In colonial America, it was common for enslaved men and women in rural areas to keep a provisioning garden to grow vegetables they most wanted to eat.

At Philipsburg Manor, which interprets an 18th-century provisioning plantation operated by 23 enslaved Africans, the slaves’ garden is full of plants African gardeners would have preferred – vegetables like black-eyed peas and sweet potatoes – as well as herbs.

Africans had an intimate knowledge of plants and other natural materials that they used to cure all sorts of ailments. So the herbs in a garden like this one served as an apothecary as well as a spice rack. (A Colonial Drugstore: Philipsburg Manor’s Herb Garden)

Philipse’s trading center has been restored to its appearance in 1750 when, in addition to the two dozen African slave it was home to several hundred tenant farmers. Their homes looked something like this. I can’t really say more because it wasn’t possible to see the interior. So, you see what I saw.

Costumed interpreters re-enact life in pre-Revolutionary times, doing chores, milking the cows, and grinding grain in the grist mill. They also act as guides.

The current tour was in the manor house, and they were waiting for them to emerge. This gave me a chance to go over and chat with them. I work with Briarcliff Manor-Scarborough Historical Society, which is only 6 miles away from the manor. They had an extensive knowledge of local history (one of them was a retired history teacher) so we didn’t have difficulties finding things to discuss.